The State of Kassala in Eastern Sudan, on the border with Eritrea, is infested with mines and unexploded ordnances (UXO), a legacy of war and conflicts between 1998 and 2005. The threat to the population is quite real and grave as the land has been turned into a source of insecurity and uncertainty. Many parts of the state are classified as dangerous areas and it is forbidden to approach them. Even now, many years after the end of the war, the remaining mines and UXOs continue to take a heavy toll on human life.

The United Nations classifies Sudan among the countries most affected by landmines and explosives. The Sudanese government recently announced that more than 2,000 people had been injured by mines, and 588 people had lost their lives since the end of the conflict. Although Sudan has signed the 1997 Ottawa Convention, or the “Mine Ban Treaty”, that prohibits the use, stockpiling, production, and transfer of anti-personnel landmines and calls for their destruction, it is yet to ratify the treaty. The government’s mine action agency estimates that 95 million square metres of mines and remnants of war had been cleared in Sudan, and more than 10,000 mines and 3,000 anti-tank weapons had been detonated since the beginning of the implementation of the UN mine action programme in 2002.

Despite this progress, people living in rangelands, pastures and agricultural land along the Sudan-Eritrea border remain under a constant threat. In addition to the loss of lives and limbs, vast areas of highly fertile arable land, the primary source of livelihood for the inhabitants of Kassala, have been destroyed by mines and become barren and dangerous. The land that these people used to cultivate and use as pasture has turned into their biggest security concern.

That is why we, as representatives of the youth from Kassala State, are renewing our call for sustained and effective action against this menace. The government of Sudan has been making a similar call to IGAD countries for a comprehensive mine action plan rather than just ‘banning’ them. Additional regional mechanisms to address this challenge of landmines must be put in place and should include compensation for the victims, speedy removal as many mines and UXOs as possible and provision of alternative livelihoods to those who are unable to make use of their land for agriculture and pastoral activities.

Comments

Related news

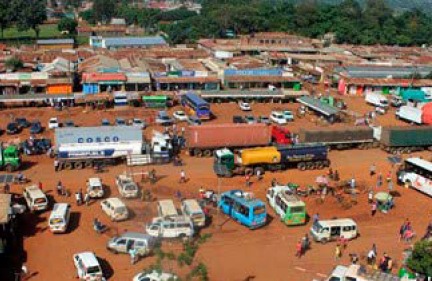

One-Stop Border Post: The Need for Public Awareness

Mohamend Wario and Haro Dulacha

October 26, 2022

A ray of hope has emerged for the people of Moyale by its inclusion in the Lamu Port-South Sudan-Ethiopia Transport Corridor (LAPSET)…

Empowering Women in Moyale: An Uphill Task

Hassan Adow and Nasra Mohamed

October 26, 2022

Women make up almost half the population of Moyale, a bustling market town spread across the border of Ethiopia and Kenya.Yet, they remain…

Formalising Informal Trade: A Modern Cross-Border Market under Construction in Busia

Gaudenciah Wanyama

October 26, 2022

Over several decades, the Horn of Africa has been recognised as a complex system of conflicts, where the conflicts in the region are interlinked and…